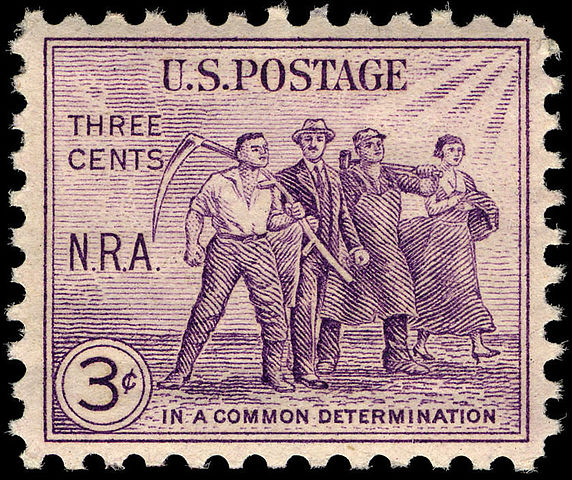

Boris Johnson has, in an interview given to Times Radio on its first day of broadcasting, made a commitment to a Rooseveltian approach to the UK. This is a striking endorsement of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, which was to be an engine of recovery for the United States from the Great Depression of the 1930s.

That a Conservative Prime Minister should choose to associate himself with Roosevelt’s achievement fundamentally subverts the economic creed of his own party. Yet he now says: We really want to … invest in infrastructure, transport, broadband – you name it. [2]

It is true that in the 2019 General Election Johnson made promises to spend big, but those commitments had the ring of pork barrel politics, made possible only in the event of a resurgent economy and liable to be modified and watered down in the context of harsh economic realities and a requirement to balance the budget. In that same election, Johnson was happy to pour scorn on the ambition of the Labour manifesto which had at its core the offer of a Green New Deal and the roll out of a fibre optic broadband network.

His current rhetoric is in the context of what everyone understands to be an impending recession of such gravity that deficit spending can be the only means of funding such an ambitious plan.

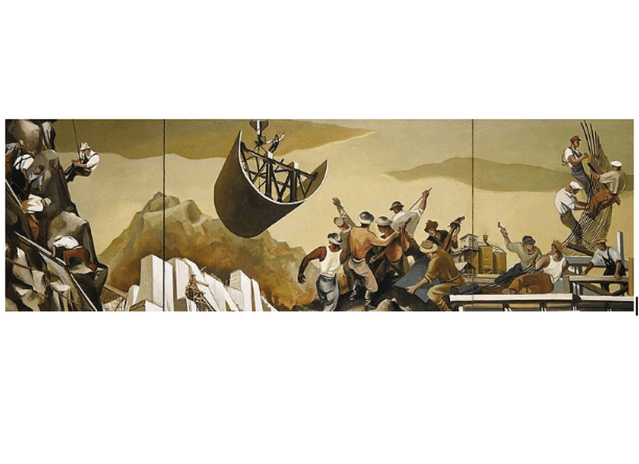

Roosevelt’s New Deal was built on borrowing in order to create work for the unemployed and destitute, by planting trees in the dust bowl; running electricity to rural communities; building the Hoover Dam to generate hydro electricity and much more. The inspiration for these policies came from the ideas of John Maynard Keynes. Even as the Roosevelt administration was moving the US economy into a period of sustained growth, spreading and increasing prosperity, the conservative economist Friedrich Hayek, guru of Margaret Thatcher, pushed back, insisting on the primacy of free markets and rejecting the idea that the state could profitably intervene in an economy.

The Cold War and McCarthyism created a hostile environment for state sponsored enterprise and the tide of economic thought was turned back to a theoretical commitment to balanced budgets, but more significantly, to favour the unfettered free market capitalism which emerged in the 1980s under the leadership of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan.

The extraordinary story of Roosevelt’s New Deal and its aftermath, is beautifully told in Zachery Carter’s recently published book: The Price of Peace: Money, Democracy and the Life of John Maynard Keynes. Carter’s book is, in fact, a history of economic ideas in the 20th century, at the foundation of which is the development of Keynes’ thought, his role in key events, and ultimately the frustration of his vision and its eclipse by a mix of ideologically driven neo-liberal free market capitalism run through with a brazen but uncredited application of Keynesian spending to fund, amongst other things, the US military and Industrial complex and foreign wars.

The early part of the book gives a colourful picture of Keynes: his academic brilliance; his promiscuous gay relationships; his connections with the Bloomsbury group, and his eventual marriage to a world famous Russian ballerina, Lydia Lopokova.

But at the outset of the First World War, Keynes became drawn into public life, providing critical economic policy advice to the British Government. Present as the Treaty of Versaille was being drawn up, he watched aghast as an agreement emerged which humiliated Germany. In his subsequent book, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, he was sharply critical of the settlement for its failure to provide conditions which could allow Germany to recover. Keynes foresaw, as a direct consequence, the failure of German democracy and the rise of autocratic rule.

Following the First World War, the British economy struggled to pay its debts to the United States, and the Conservative Government became convinced that it was necessary to return to the Gold Standard. In direct contravention of Keynes’ advice, Winston Churchill, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, was responsible for once again pegging sterling to gold.

Keynes was scathing and responded in a pamphlet, The Economic Consequences of Mr Churchill, in which he disingenuously asks: Why did he do such a silly thing? …Partly, perhaps, because he has no instinctive judgment to prevent him from making mistakes; partly because, lacking this instinctive judgment, he was deafened by the clamorous voices of conventional finance; and, most of all, because he was gravely misled by his experts. [3]

Churchill himself, in 1930, came to recognise the folly of his policy: Everybody said that I was the worst Chancellor of the Exchequer that ever was, and now I’m inclined to agree with them.

Carter’s book quotes liberally from Keynes: his letters, his journalism, his books. It is clear that Keynes had a gift for popular communication, with writing that was both clear and witty, but acknowledged as his masterpiece was The General Theory of Employment and Money, a book written expressly for professional economists, uncompromisingly dense and impenetrable to the common reader. Needless to say, I have not read it, and yet the central ideas of Keynesian economics seem remarkably straightforward: that a democratic government, in command of a currency, has the power to activate unused or misdirected labour, and indeed all resources, at its disposal, to achieve any great or necessary project that may be in the general interest. Whatever is possible may be done, and where the money is not immediately available, but the resources are, then it is reasonable to create the money by such means as are available.

The most visionary aspect of Keynes work was his proposal to the Bretton Woods conference in 1944, to create an international clearing currency, the Bancor, against which national currencies could be pegged and which could be managed in such a way as to ensure fair trade conditions across national boundaries. Sadly Keynes, in deteriorating health, was unable to persuade the conference to accept his proposal and instead the post-war economic settlement was built on the foundation of the US dollar being convertible to gold. Keynes accepted this as a workable solution, and the system survived until 1971 when the US, under the presidency of Richard Nixon, unilaterally withdrew, resulting in an international currency market, which could never offer a stable and fair international trading environment.

For anyone with a serious political or economic thought in their head, who fears for the future of democracy and observes the emergence of political forces unwilling to confront or even acknowledge the huge challenges which face us, this book should inform public debate and deserves to be widely read.

But returning to my opening theme: the commitment of Boris Johnson to a “Rooseveltian” project. I share the widely expressed skepticism that his conversion may not be sincere. George Eaton, in his New Statesman article Why it’s absurd for Boris Johnson to compare his spending plans to FDR’s New Deal points out, that: As a share of the economy, Johnson’s spending plan is 200 times less ambitious than the New Deal. [4]

It is increasingly clear that a Prime Minister, trapped by the COVID19 pandemic and inevitable recession, has few options at his disposal. The economic theories of Hayek and his successors have run out of credible policy ideas. Keynesianism is resurfacing as an economic model with something concrete to offer for these troubled times. But there is a deeper concern in that the crisis with which we are confronted is not merely an economic recession.

Keynes, in a typically vivid but ironic example, suggested that, in the event of recession and unemployment, the Treasury could fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coal mines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up again (the right to do so being obtained, of course, by tendering for leases of the note-bearing territory), there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing.

However, in our current circumstances of climate crisis, any investment which does not align with the objective of reducing our carbon footprint, would be worse than nothing and a more considered and constructive response is required. It is obvious that many in the Conservative Party will be happy to invest in fracking, new roads and airports and housing built to standards dictated by the narrow vision of construction companies. Such is the current character of the party Johnson has committed to build back better, to do things differently. The real challenge we face is to create a carbon neutral economy and a world fit for all citizens to live a sustainable and good life and it is not at all clear that the Conservative Party is capable of delivering this.

Yet the Labour Party must give a qualified welcome to Johnson’s “Rooseveltian” commitment for this is the basis on which its own ambitious commitments were set out in its 2019 Election manifesto. Labour must now hold the Prime Minister to account and, if possible, guide him towards his Keynesian destiny and the glorious place in British history which he so earnestly craves. This would indeed be a strange and unexpected way for Jeremy Corbyn and John Mcdonnell’s reputation for economic competence to be rehabilitated.

If however, as seems all too probable, he falls short of the scale of his own rhetoric, or is obstructed or brought down by his own party, then Labour must stand ready to do the job themselves.

Reviews of The Price of Peace, Money, Democracy and the Life of John Maynard Keynes

References

[1] The Price of Peace: Money, Democracy, and the Life of John Maynard Keynes Kindle Edition

[3] https://www.gold.org/sites/default/files/documents/1925jul.pdf

[4] https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/economy/2020/06/why-it-s-absurd-boris-johnson-compare-his-spending-plans-fdr-s-new-deal

Thanks to Elaine for assistance with research and proof reading.

Featured Image