A Reflection on the Dangers of Moral Certainty

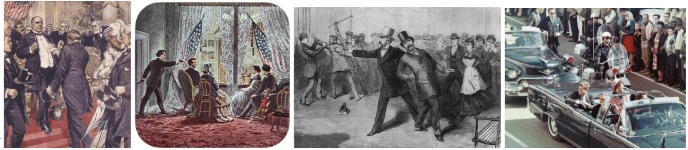

Name the four US presidents who have been assassinated!

That’s a challenge which one might expect in a pub quiz. Team members, such as myself, who have been roped in at the last minute to make up the numbers, will confidently list Kennedy and Lincoln. Naming the other two would have to be left to the real quizzers in the team.

Wikipedia helps out and reminds me that the forgotten pair were James A Garfield, assassinated in 1881, and William McKinley, assassinated in 1901. [1]

Both individuals survived the immediate trauma of being shot. McKinley lived for a week and then his wound became gangrenous. He quickly went into decline and died. Garfield, on the other hand, survived for over eleven weeks and should have recovered had it not been for his doctor’s unsterilised digital probing of his wound in what were – for Garfield – extremely painful attempts to extract a bullet which might better have been left in situ.

Diverting though these facts are, my interest in the events is concerned largely with our retrospective assessment of these four Presidents. Lincoln and Kennedy, live on as historical figures of great consequence, whilst Garfield and McKinley have been largely forgotten.

Well that’s not entirely true. In an article for the New Yorker Daniel Immerwahr speculates on Why Donald Trump Is Obsessed with a President from the Gilded Age. This turns out to be President McKinley. A quick skim of McKinley’s Wikipedia page suggests a somewhat isTrumpian slant to his achievements. He raised tariffs, promising protection for American business. He offered a good deal on civil rights for people of colour, but delivered little. He was complicit in the annexation of the Republic of Hawaii saying “We need Hawaii just as much and a good deal more than we did California. It is manifest destiny.” [2]

It was his own destiny to end up on the receiving end of an assassin’s bullet fired by Leon Frank Czolgosz, an American wireworker and anarchist.

McKinley’s presidency began in March 1897 and he was assassinated on September 6th 1901, early in his second term. Garfield’s presidency, by contrast, lasted less than 6 months. He was gunned down before he had really got started. And yet there is a case to be made that, of all these Presidents, Garfield, the most easily forgotten, was in fact the greatest of them all.

Garfield’s Wikipedia page makes it clear that his character and policy ideas are not above criticism, but for the purpose of my argument I prefer to focus on the relatively unblemished representation of his character offered by the Netflix serial Death by Lightning. [3, 4] Michael Shannon provides the gravitas for the part of Garfield and Matthew Macfadyen brilliantly evokes the quixotic and delusional character of Garfield’s nemesis, Charles Guiteau.

A key element of the story is that Garfield never intended to become President. He knows the Republican Party in that era to be deeply and irremediably corrupt. He agrees however to give a speech on behalf of a candidate who he believes cannot win the Republican nomination for the Presidency, but who may perhaps unsettle some of those who in that moment appear to be completely dominant.

In fact this speech resonates with the assembled delegates and becomes the platform from which, against his better judgement, Garfield is first proposed and then adopted as the Republican candidate for the Presidential election.

That much is remarkable and suggests someone with both modesty and a striking rhetorical presence. Garfield goes on to triumph in the presidential election. However, he has been shackled to a corrupt Vice President, not of his choosing, Chester A Arthur. Vice President Arthur is in league with obstructive opponents led by corrupt New York Senator Roscoe Conkling. Things do not go well for Garfield. And then he is assassinated.

Before laying out a case in favour of Garfield’s significance, I will mention a detail from the film, almost certainly fictional, but which suggests evidence that Garfield, at the very least, made a profound impression on those working most closely with him in the White House.

Guiteau, a kind of stalker-like figure, is attempting to persuade members of the President’s entourage that it is important for him to speak directly to Garfield. He encounters a young presidential aide. With an apparently genuine curiosity Guiteau asks the young fellow: “What kind of person is the President?” The assistant pauses and then replies with obvious sincerity: “He is the greatest man I have ever known.” Suffice to say, Guiteau does not get what he wants and retreats to reflect bitterly on the insult.

The character of Vice President Arthur is critical to understanding Garfield’s presidency. Arthur is a moral weakling, clearly fearful of Conkling and openly defiant in the face of the President’s attempts to introduce reforms. And yet Garfield treats his Vice President with consistent patience and respect. In essence, he says to Arthur: “I believe you are a better person than this.”

Arthur is clearly rattled by the faith the President has in his debased character but, in the first instance, continues to dance to Conkling’s tune. In the event of the assassination however, Arthur experiences a kind of nervous collapse in which he acknowledges his own depravity and insists that he is unfit to be president. Garfield’s widow, on hearing this pathetic confession, stands firm in the face of Arthur’s hysteria and insists that he master himself. Eventually the Vice President sets to work on delivering Garfield’s programme of reform.

I thought of this story when recently a friend drew my attention to Rutger Bregman’s book, Moral Ambition. Early in the text Bregman explains: “Moral ambition is the will to make the world a wildly better place.” That sentence for me is damaged by the inclusion of the word “wildly”. However, I persisted, and despite some reservations – which I shall come to – I’m glad I did. [5]

Whilst reading the book I became aware that Rutger Bregman was giving this year’s Reith Lecture, under the title Moral Revolution. On tuning in to listen I found the lecture more immediately to my taste than his book. [6]Indeed I think it reasonable to assume that Rutger Bregman wrote his books in his mother tongue, Dutch, and that consequently what I was reading was a version of the original which had been souped up for the US market.

But leaving these considerations aside, the motivation of the aforementioned assassins is worth considering. It is not clear that any of them were paid for what they did; rather they were all acting on their idea of what was the right thing to do. All four notorious assassins set themselves an ambitious and morally framed objective; to murder a President. All were, consequently, to lose their own lives.

Perhaps the point may be made clearer if we consider for a moment Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg’s failed plot to kill Hitler, for which he also was to lose his life. In that particular instance there is fairly widespread agreement that von Stauffenberg’s ambition to end Hitler’s life was heroic.[7]

In the final analysis, the mere fact that an action is framed morally tells us little or nothing about the quality of reflection or questioning or doubt or humility of the individual who has done the deed.

Ambition is a word tinged with the pejorative. Those who succeed as a result of ambition do so as much because of this quality as any other they may possess; such as honesty, integrity, ability. What shines through in Garfield’s case is not ambition, but honesty and integrity. It seems unlikely that, once he had won the Presidency, Garfield was untouched by Presidential ambition. After all, he set about introducing reforms intended to break the corruption he saw around him. It is not ambition per se with which I quibble, but ambition untempered by doubt.

Politicians in the current era are universally despised despite their frequent claims to be motivated by a desire to serve the public and to make the world a better place. I don’t wish to indulge in the modern reflex to demonise politicians, but quite possibly it is a surfeit of ambition that has transformed them in the public mind from servants of their constituents into self-serving and untrustworthy parasites. Just to be clear: though this may be my own view of a few of them, it is not my view of politicians in general.

Rutger Bregman builds his case in favour of moral ambition on an extensive cast list from history; those who fought for an end to slavery or votes for women or rights for people of colour in the USA. Some of these heroic figures are well known to us; others lived and died in relative obscurity, and did not see the changes for which they had fought hard and sacrificed much.

I was very happy to be reminded of the courage shown by this heroic roll call and I am very much in agreement that their achievement deserves celebration. But then I also think of the moral ambition which accompanied European and British Imperialism and its brutal attempt to “civilise” other peoples by the systematic undermining of their culture, language and beliefs.

I stumbled across a useful perspective on this matter a few weeks ago when listening to the Professor of Political Theory at LSE, Lea Ypi on BBC Radio 3’s Private Passions. She describes herself as “a philosopher in activist mode” not just reflecting on the world but also hoping to inform and change it by answering questions; questions such as what is required to live a good life and what is justice. Crucially she adds: “there is a moral yearning underpinning it.”

She went on to suggest that this “yearning” is commonplace in children and that children are not afraid of asking difficult questions but that we are inclined to lose this fearlessness as we grow older.

Lea Ypi grew up in Albania and as a child witnessed the fall of Enver Hoxha. As she observed to Michael Berkeley: “All I had in that period were questions and so I thought, ‘What can I study that will enable me to ask better and better questions?’ And the answer was philosophy.” [8]

“Moral yearning” suggests an openness to different perspectives on what may be right and wrong and a willingness to reflect with humility on moral questions wherever and however they occur. It strikes me that the didactic and morally ambitious character of our education system may carry much of the responsibility for extinguishing our childhood yearning to seek after moral truth. Moral yearning, is I would suggest, a quality to be protected and nurtured rather than something which can be taught.

But my intention in saying all this is not to take down Rutger Bregman but rather to suggest that when moral ambition gets the better of moral yearning, we may have a problem.

Endnotes

1] Wikipedia List of United States presidential assassination attempts and plots [Source of images used in this post.]

2] Why Donald Trump Is Obsessed with a President from the Gilded Age

3] Wikipedia James A. Garfield

4] Netflix Series – Death by Lightning

5] Book – Moral Ambition – Rutger Bregman

6] Reith Lecture – Moral Revolution, Rutger Bregman

Very thoughtful and interesting piece Stephen. Many thanks. As a singer you may be interested in the songs that relate to McKinley, such as by the New Lost City Ramblers (Battleship of Maine). I think there are a lot more, including one by Al Stewart. Bit of a project! all best David